- Home

- kucy a snyder

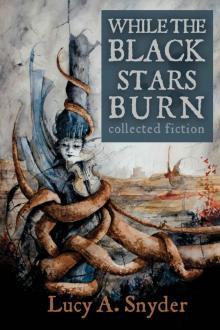

while the black stars burn

while the black stars burn Read online

WHILE THE BLACK STARS BURN

While the Black Stars Burn © 2015 by Lucy A. Snyder

Published by Raw Dog Screaming Press

Bowie, MD

All rights reserved.

First Edition

Cover: Daniele Serra

Book design: Jennifer Barnes

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-935738-77-0

Library of Congress Control Number:

www.RawDogScreaming.com

WHILE THE BLACK STARS BURN

Lucy A. Snyder

Table of Contents

Mostly Monsters

Spinwebs

The Strange Architecture of the Heart

Approaching Lavender

Dura Mater

The Still-Life Drama of Passing Cars

Through Thy Bounty

Cthylla

While the Black Stars Burn

The Abomination of Fensmere

The Girl With the Star-Stained Soul

Jessie Shimmer Goes to Hell

Fable Fusion

About the Author

Publication History

Mostly Monsters

My bones dragging like lead rods, I trail after my girlfriend on her quest for yarn in some huge, fluorescent craft barn. The lights are buzzing brain bleach. I spy with my bloodshot eye modeling clays in kid-friendly buckets, bright packs of rainbow logs. I want them desperately. I want to grab a pack and run off to some dark, quiet room and feel the cool, greasy clay squish and roll beneath my fingers. But even the cheapest, tiniest pack is $10 and my car needs gas and my husband’s surgery is coming up and there’s no room in our little house to build anything. I pass on by.

In my girlfriend’s car, I close my eyes in the summer heat and remember the smell of the clay as I worked at my craft on a card table in the back bedroom of my father’s house. The walls seemed to hold their breath before the air conditioner thumped on. In that dusty, silent room of a ranch house surrounded by ancient neighbors who weren’t anyone’s grandparents, I used to build my friends: dragons and squires and heroines, but mostly monsters.

My mother started me on monster making. When I was little I had vivid dreams, sometimes terrifying ones, and I told her about the scary creatures who came to me at night.

“When you see them, just make friends with them,” she said cheerfully. “Then you’ll see they’re not so bad.”

My mother was a lucid dreamer, and when I was older I realized she was encouraging me to take control of my nightmares. But I was never any good at that, not even as an adult, and when I was five I didn’t understand. How would I know when I’d see them again? How could I possibly wait for that? So I recreated the monsters in clay to make them fight each other and not chase me through the woods or through strange houses with endless corridors.

I made my own Godzilla in gray and green clay and a muscular Wolf Man in brown. There was blue, eight-armed Tentacles (pronounced like Hercules), whom I started dreaming about after I glimpsed the giant squid scene in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea on TV. And there was Eyeblob, a formless mass of eyeballs that had chased me ‘round and ‘round in my dreams ever since I could remember. Playing with my creations didn’t stop the rare nightmares, but it didn’t make them worse, either, and after all there wasn’t anybody else to play with.

One evening, my parents forgot why they’d told me to keep the clay in the back room and they let me bring my creations out to play on the coffee table while they watched television. My friends menaced one another in the flickering blue light. Afterward, it was time for bed. I put my monsters away and soon I was soundly out in the kind of sleep only a kid can have.

Suddenly my father burst into my bedroom, shouting about the coffee table. The clay left smudges on the glass! He dragged me into the living room. Disoriented, terrified, I was sobbing, pleading. He threw a napkin at me and made me scrub at the stubborn smudges with a shivering hand. I couldn’t keep the snot and tears from dripping off my nose onto the table and that made him angrier, louder. My mom hovered nearby, quietly asking him to stop. Not intervening. She didn’t tuck me in afterward. For a long time, I thought she’d done all she could to stop him.

Thirty-seven years later, I tell a perfect stranger in a therapy room that, if it had been me, I wouldn’t have just stood by making helpless mouth noises while my bad marital choice did that to my kid. The moment he headed to the bedroom, I’d have told the fucker that the Windex was under the sink if the smudges were such a catastrophe. And if he’d opened that door and said anything more than “I love you” he would have spent the night outside with the bats.

The perfect stranger asks me how my relationship with my father is. We aren’t friends. He asks how my sleep is. It’s shit.

Every night I wake up in a panic, thinking I have forgotten something critical and now a man is coming into my room to punish me. Kill me. Every. Fucking. Night. Sometimes six or seven times a night. And when I’m awake, I feel as though I’m always holding my breath, waiting for the thump.

The perfect stranger tells me I have PTSD. He says that pills—which I never asked for anyhow because I hate how they smear my brain—won’t help. I need complex, long-term therapies to repair my broken sleep, and my insurance mostly won’t cover it. The bills would be a devouring beast.

My girlfriend drives me home. I roll the letters around in my head. PTSD. From that? One harsh wakeup in a silent house? Seriously?

But it wasn’t just that. The kind of guy who would roust his kid screaming over a few clay smudges wouldn’t do only that. His violence was rare, but memorable, the work of some great anti-artist slowly building me up only to tear me back down. I marvel again that my mother stayed with him the decade it took for me to be conceived, and I also want to weep because she stuck with him ‘til her death, thirty-five years more.

Girlfriend drops me at the curb and I go inside, quiet so I don’t wake my husband from his nap upstairs. Our coffee table is scarred wood, piled with prescriptions and junk. I climb the stairs, take off my clothes and slip into the sheets, my body spooning against my husband’s perfectly. He shifts, murmurs, starts to snore again. I don’t sleep. I think of the deplorable clutter on the coffee table, and our bills, and wish I’d bought a bucket of clay anyhow.

Finally I get up and go to my computer in our back bedroom. There are smudges on the monitor screen. I don’t wipe them off. I take a deep breath, and start to write about dragons and squires and heroines, but mostly monsters.

Spinwebs

Adira held the cabbage-sized, iridescent amber egg close to her chest while Mama Silklegs twitched and curled on the hay-stuffed mattress. The gentle old spinweb was wheezing in obvious agony, the lids over her four eyes swollen. Mama curled her eight legs under her in a strange way; the tears blurring Adira’s eyes made the old spinweb look like a massive copper daisy sagging on her parents’ bed. A sour odor like spoiled chicken broth hung in the air.

Solemn, her father dripped milky poppy tonic from a goatskin into Mama’s round, toothy mouth. He’d given Adira’s grandmama the same tonic when her belly swelled as if she were with child but no child ever came. Her grandmama said the tonic took away the pain in her bones and helped her sleep. Adira hoped it would help Mama, too.

She wanted so badly to be strong like her parents told her, but Adira couldn’t stop the tears burning in her eyes. Even replaying within her mind the ridiculous songs her Aunt Ruthie taught her didn’t help. Her brother Moshe and sister Dalia were weeping openly, clutching their eggs like they used to hold tight to their baby blankets during thunderstorms.

“Don’t squeeze them so! Just keep them warm!” Gray-faced, her mother wiped h

er own eyes on her apron. Her own health failed when Mama got sick; their father said it was from worry but Adira knew it was more than that. Just a year ago her mother had been a big, hearty woman who could heft 60-pound rolls of silk damask over her head into the merchant’s wagon. While her will remained strong, her body was frighteningly thin. Adira feared that a strong winter wind might blow their mother away.

She put a shaky hand on Adira’s shoulder. “It is the way of things. Having babies is hard on her, just like it is for us.”

The girl silently vowed to never have a baby. “I don’t want her to die.”

“None of us do, my little mouse. She is a queen amongst the spinwebs; she has lived a long and wonderful life and provided for five generations of our family. There will be none like her again, but she has left us three beautiful eggs, and she trusts us to raise her babies. None could hope for so great an honor as this.”

Moshe sniffled. “Not even Prince Helmut?”

Mother snorted. “Certainly not he.”

Their father emitted a strangled noise somewhere between a nervous laugh and a muffled yelp. “Darling! Do not tell the children such things; they might repeat them outside, and then what would happen?”

Muscles bunched at her mother’s gaunt jaw. “I forgot myself. Children, as your father says: say nothing of Prince Helmut’s greed and villainy.”

“Darling!”

“I take it back,” she sighed. “Children: forget!”

Mama Silklegs emitted a sudden pained shriek and thrashed on the bed, and in almost the same moment their mother clutched at her chest and fell to her knees, her face contorted in pain.

*

Adira sat watch over her mother while her father and the weavers and dyers dug a grave for Mama in the family graveyard. The girl’s stomach ached with fear. Her mother fainted when Mama died, and none could wake her. Mama had to be buried before sunset, and digging such a massive grave took almost all the able-bodied people on the magnanery. So her father put her mother in Adira’s bed and told the girl to fetch him if her condition worsened.

She hugged the egg in her lap. The iridescent shell was hard like oil-boiled leather, but she could feel the baby spinweb moving inside, stretching the walls. It would hatch soon. She knew she had to take the best possible care of the egg, not just out of respect for Mama but also because the only spinweb who remained, Auntie Goldbelly, produced barely a quarter of what Mama had before her egg sickness. They grew plenty of vegetables and raised goats, but if they didn’t sell enough silk, they wouldn’t be able to pay Prince Helmut’s new tax. The dairy farmer next door hadn’t been able to pay after his cows poisoned themselves on ragwort, and soon the prince’s guard came with crossbows and swords and seized the farm. Adira’s father sheltered the evicted farmer and his family for a few months, but they left to seek a better fortune in Esterland, whose queen was said to treat her subjects fairly.

“How is she?” Her father stood in the doorway, drying his hands on a dishcloth. Graveyard mud stained the knees of his grey silk trousers.

“Much the same,” Adira replied, feeling an ache in her chest. “I tried singing her favorite song, but it didn’t help.”

Her father moved to the head of the bed and gently lifted her mother’s eyelids and peered down at her constricted pupils. With a sad shake of his head, he stood up, tugging on his long black beard as he always did when he was upset.

“Is it bad?” Adira asked, feeling herself tear up again.

“It is,” he replied. “Losing Mama was a terrible shock to her soul. When Mama hatched, she first bonded to your great-grandmother, who was a girl no older than you. Spinwebs live so long that they are accustomed to losing their people, but for your mother to lose her Mama? It’s a dire thing. Your mother surely felt it as keenly as if she herself had died.”

He cleared his throat. “I can make an elixir that might revive her, but I need a quantity of tutsan, and the hills are barren of flowers.”

The girl sat up straighter, thinking. There was a plan. She could do something instead of just sitting helplessly. “Won’t the apothecary have powdered herbs?”

Her father paused. “Fresh would be best, but I could use dried petals....”

“Dalia could stay with mother, and I could go fetch them for you?” Adira loved the apothecary shop with its colorful glass bottles and exotic smells and mysterious compounds. She immediately felt a little guilty for wanting to be there instead of at her mother’s side. But not guilty enough to take back her suggestion. “It’s not far. I wouldn’t be gone long.”

“All right.” Her father sounded reluctant. “I suppose it is only a mile away. But take Moshe with you. And a knife. And mind the eggs! Do not let anything happen to them. I have harnesses for both of you....”

*

Their father went through his chests and found egg harnesses made from thick sheepskins, leather straps and shiny brass buckles. He helped them put on the harnesses and strap the eggs inside the cozy sheepskin cradles. He gave Adira one of his hunting knives, and she secured the sheath to her belt.

Moshe giggled when she buttoned her long blue padded silk coat over the harness. “You look like you ate a barn!”

“So do you!” she replied, which did nothing to stifle his laughter.

“Children, be serious.” Their father drew them in close. “Your mother would skin me if she knew I was letting you go out with the eggs. I should send one of the weavers or dyers, but the truth is that I cannot spare them from their work. I am terribly afraid that we won’t get a good price for our cloth, so we need to make twice as much to ensure that we have the tax money when the soldiers come next month.”

He paused, and Adira knew his unspoken fear: that if they waited to get the ingredients for the elixir, her mother would not recover.

“We will be fine.” She squared her shoulders, determined to stay as brave as she could. “We’ve been there a hundred times! And there are so many soldiers on the road that nobody has seen a bandit in months.”

Her father frowned at the floor when she mentioned soldiers. “I suppose that’s one silver lining.”

Then he looked at Adira: “Are you ready?”

She stuck her hand in her right coat pocket, turned it out, and ripped a hole in the seam so she could draw the knife if she needed to. “I’m ready.”

*

Just inside the city wall, Adira and Moshe encountered a group of older boys in black students’ robes clogging the road, laughing and shoving one another. Her heart beat faster; big boys were trouble. She tried to lead Moshe around the gang, but one, the tallest boy, noticed them and threw out a gangly arm to block their way.

“Ugh,” he said, wrinkling his nose at them in exaggerated disgust. His blond hair fell in fashionable ringlets around his face. She could tell from the cut of his tunic beneath his robe that his parents were wealthy burghers.

“You stink of spiders,” he said, stepping aggressively close.

Adira squeezed Moshe’s hand and gave him a quick, meaningful glance. Say nothing.

Moshe gave her a quick nod in reply and stared down at his boots.

Another boy stepped up. He had close-cut brown hair and the wispy beginnings of a beard. “Spiders are an abomination. We shouldn’t allow people who live with abominations.” He pronounced it as though it was the first really long word he had learned in school and he’d been dying to try it out.

Adira tried to swallow her anxiety and aggravation. She wanted to tell him that comparing her family’s spinwebs to common house spiders was like comparing humans to field mice, but she knew he’d never understand.

“Spinwebs made your robes and your mothers’ fancy dresses,” she replied. “Maybe you should all go naked if you think they’re so bad.”

The second boy blushed and stepped back, but the first boy scowled down at her.

“My father dines with the prince, and he says foul daggles like you have no place in our kingdom. Your days here are few,”

he whispered.

“I’m sure that’s true.” Her nerves sang with fear and anger. The feeling made her a little sick, but it felt good, too, like she was finally really alive. Her own emotions scared her even more than the boys did, so she tried to push all the fear away. She slipped her hand into her pocket, feeling the smooth knob of the knife’s pommel, wondering if the bully was the sort of soft boy who would panic at the sight of his own blood, or if he would fly into a murderous rage. Either way, the guards would surely come. And then what? Her mind flew over a hundred different scenarios, and they all seemed bad or catastrophic. The guard and townsfolk would rally behind the boys, not her and Moshe.

Her spinweb kicked inside its shell, reminding her of her duty. No. She couldn’t resort to the knife, not here.

She forced a meek, unassuming smile. “But since our days are numbered, can we please go about our business? Surely the prince will expunge us and you will never have to see us again.”

“But I have to smell your stink now.” He eyed her as if she was a bit of cow dung that refused to be scrubbed from his shoe. “Ugh, I can’t see how you live with it! Is it coming from your clothes? What have you got there under your coats?”

Adira gave Moshe’s hand another squeeze, and neither of them spoke.

“What have you got?” the blond boy demanded. “You better tell me, or I’ll call for the guard!”

She couldn’t think of a good lie, so she told the truth: “Spinweb eggs.”

He frowned. “What?”

“Eggs. Our mama spinweb is having babies, and we’re keeping them warm for her,” she said.

“Nasty,” the second boy hissed, and he and the others backed away a bit, staring at the egg bulges as though they might suddenly hatch and swarm the boys.

while the black stars burn

while the black stars burn